The body at Somerton Beach

I wrote this piece about the Somerton Man a few years back for a now defunct magazine called The Weekly. A lot's been discovered about the Somerton man since, but the basics are here ...

On the 30 November 1948 at Adelaide Railway Station a tall, tanned man carrying a brown suitcase bought a second-class ticket for the 10.50 am train to Henley Beach. He walked onto the platform and handed his ticket to the conductor. Then he walked a few steps, or perhaps all the way to the platform, before deciding not to board the train. He left the platform and checked his suitcase at the cloakroom, taking ticket number G52703.

So begins the story of the Somerton ‘mystery man’, one of the strangest unsolved murders (or suicides) in Australian history. To this day no one knows the man’s identity, where he was from, what he was doing at Adelaide Station, what job he had, why he was fascinated with codes, and poetry, if he was a spy or a transvestite, or even how he died.

So, it’s mid-morning, and he’s missed his train. Why? Maybe he was running late, or perhaps he had a change of mind about his destination. Was someone waiting for him at Henley Beach? Someone he couldn’t face? Did he owe them money? Or did he have a change of heart about selling government secrets to a Russian spy? All very dramatic, but nothing’s ruled out with the mystery man. Next, he climbed the concourse stairs to North Terrace, crossed the road and waited at a bus stop outside the Strathmore Hotel, eventually catching the 11.15 am bus to Glenelg and Somerton.

That evening at 7.00 pm a man named John Lyons was walking along Somerton Beach with his wife. They noticed a man lying on the sand with his head against the seawall. As they passed him, they saw him move his right hand as if he were smoking a cigarette or trying to wave to them.

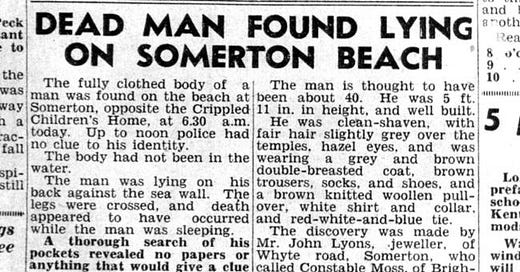

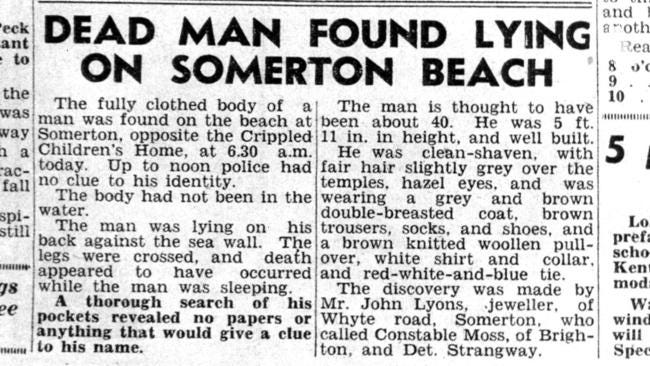

The following morning, December 1, John Lyons returned to the beach for a swim at about 6.30 am and saw the same man sitting motionless against the seawall. Some reports have John Lyons discovering the body and others have him joining a group of people who had already made the discovery. Some sources say the body was discovered fully horizontal (as per the previous evening) and others have the man sitting up against the seawall with his head slumped. Either way, it was John Lyons who rushed home to ring the nearby Brighton Police Station.

Lyons quickly returned to the beach. Constable Moss, the officer-in-charge at Brighton, soon joined him. He found the body of a tall, clean-shaven man in his early forties wearing a coat, brown trousers, white shirt, a knitted pullover and a tie. Moss found no signs of a disturbance or violence. Upon examining the man’s clothes, he noticed all of the labels had been removed. His left arm was stretched out beside his body, but his right arm was bent up. A half-smoked cigarette was found sitting on the right collar of his coat. Apart from the unused railway ticket to Henley Beach, a used bus ticket to Glenelg and cigarettes and matches, his pockets were empty. There was no wallet or keys and the claim to his suitcase was missing.

Most of the newspaper and magazine articles written about this case rule out suicide straight away. Who gets up and shaves just before killing themselves? To counter this we could say that shaving is a habit and if the man was contemplating suicide the familiarity of this routine may have been helping him cope with his decision. The same applies to the jacket and tie. Who dresses up for death? Again, this may have been how men of his class or profession (whatever that was) dressed. Habit. Familiarity. Or maybe this does suggest foul play. After all, why deposit a case you’ll never claim?

The dead man was taken to Royal Adelaide Hospital where it was concluded he died around 2.00 am. Two days later a post-mortem was conducted. The coroner claimed he could find no cause of death. The man’s stomach was congested with blood (a sign of poisoning) but no poisons were found in his body. This might point to a murderer with a good knowledge of poisons but the police at the time had no way of telling what these might be or how they were administered. The post-mortem also showed the man had no puncture marks and his last meal had been a pasty (and who eats a pasty before killing themselves?)

An inquest into the death, handed down in June 1949, stated: ‘The stomach was deeply congested… There was blood mixed with food in the stomach. Both kidneys were congested, and the liver contained a great excess of blood in its vessels.’ Dr John Dwyer, a pathologist who examined the body, suggested that this man’s death could not have been natural. He said the heart had stopped beating, or more correctly, had been stopped, probably by a very uncommon poison – one that had already disappeared from the body.

On the morning of 2 December, The Advertiser reported: ‘A body, believed to be of E.C.Johnson, about 45, of Arthur St, Payneham, was found on Somerton Beach, opposite the Crippled Children’s Home yesterday morning. The discovery was made by Mr J. Lyons, of Whyte Rd, Somerton. Detective H. Strangway and Constable J. Moss are enquiring.’ Mr Johnson contacted police the next day to explain that he was very much alive, thus becoming the first of many dead-ends.

The police fingerprinted the man but couldn’t find a match on their records. There were no scars or distinguishing marks on the body. They distributed the man’s photo to newspapers but there was no response from the public. Soon after they sent photos and fingerprints to every police force in the English-speaking world, without a single positive reply. As the police had no scientific branch in the 1940s the cigarettes found on his body were never tested for poison. The brand of cigarettes (Kensitas) was different to the packet they were found in (Army Club). This may have indicated that the man had borrowed or bought stray cigarettes from someone else or, less likely, had (possibly poisoned) cigarettes substituted without his knowing.

As detectives at the time pointed out, the baffling thing about this case was not the lack of evidence but the surplus. Unfortunately, most of this evidence led nowhere. In fact, much of it was contradictory and distracting. It was as though Agatha Christie had set out to write a novel without knowing the ending. As though she got halfway through and gave up in confusion.

The man was embalmed and kept in a deep freeze at the city morgue. Over the next few months fifty people viewed his body. They claimed he was a long-lost brother, an old bowls partner, a Bulgarian, a missing son. All of these leads were investigated and dismissed.

Adelaide in 1948 was still an innocent place. On a Sunday afternoon you could watch pole-sitting (cupboard-sized rooms mounted on poles, where the brave stayed for days) or the Sunday Advertiser Beach Girl Quest at Glenelg Beach; then you could listen to Clyde Cameron addressing Speaker’s Ring at Botanic Park before wandering up to the City Bridge to watch divers promoting the Advertiser Learn-to-Swim School. During the year Moore’s department store burnt down and the Glenelg jetty was wrecked by a storm that washed HMAS Barcoo ashore at West Beach. Rationing was still in place, and a wave of migrants from Britain, Poland, Latvia and other European countries were moving into Nissen huts in hostels at Pennington, Woodside and Glenelg North. For most of the winter local stockbroker Don Bradman was off in England with his Invincibles, but Premier Tom Playford was firmly in charge, as he would be for another twenty years.

In January 1949 the unclaimed suitcase was discovered at Adelaide Station. The luggage label had been removed. Clothing in the case matched that worn by the man although, again, the labels had been removed. The case contained a roll of thread matching that used to stitch buttons on the man’s trousers; a dressing gown; size seven red felt slippers; four pairs of underpants; two ties; a pair of trousers containing three dry cleaning stubs (1171/1, 4393/3 and 3053/1) inside a pocket; a coat; two shirts; a singlet. The numbers on the stubs were circulated to dry cleaners around the country but no one recognised them, although one suggested they might be of English origin.

Several items carried the name ‘T. Keane’. Police believed this might have been Tommy Keane, a local sailor. Keane couldn’t be located so a few of his old shipmates were taken to view the body. All of them said it wasn’t him.

Police were at a dead-end. This gave the local press licence to invent. The man became a Cold War spy (the Woomera rocket range was still being built), a runaway circus performer or a jilted lover ending it all.

The suitcase also contained a brush used for stencilling and a pair of scissors and a knife with sharpened points. These were similar to those used on merchant ships by Third Officers responsible for stencilling cargo. The case also contained shaving equipment, boot polish, handkerchiefs, a scarf, a towel, a teaspoon and airmail envelopes with no stamps. Detectives concluded he was probably a ‘man of the sea’. They checked every ship in port around Australia but there were no reports of any missing crew.

The big and little toes on the mystery man’s feet were pushed in. The detectives wondered whether he had worn high heeled or pointed shoes. They checked local and interstate ballet schools and theatres but found nothing. The press suggested he might have been a transvestite, but there was no other evidence to support this.

In April 1949, just as the investigation had stalled, a tiny rolled-up fragment from the page of a book was found in the man’s trouser fob pocket with the words ‘Taman Shud’ (‘the end’) on it. An Advertiser reporter told police that this was from a nine-hundred-year-old poem called The Rubaiyat, by Persian poet Omar Khayyam. The poem was about living life to the full and having no regrets. The last verse before these words reads,

And when yourself with silver foot shall pass

Among the Guests Star-scattered on the grass

And in your joyous errand reach the spot

Where I made one – turn down an empty glass.

Police immediately began searching for a copy of The Rubaiyat that had the last page missing. When this latest clue was revealed in the press a local doctor (or perhaps chemist, for some strange reason his identity was never recorded by police) came forward. This man claimed to have found a copy of this book thrown onto the back seat of his car when it was parked outside his home at Somerton Beach on the night of November 30. A clipped section on the final page exactly matched the rolled-up piece of paper in the mystery man’s pocket.

The public was becoming intrigued. Surely this was a Bulgarian transvestite spy pumped full of poison by a secret government agency which had gone to great lengths to confuse the public and police, and to leave everyone with a mystery that wouldn’t so much hide the man’s demise as publicise it internationally. The government had thought it all through, from the selection of an obscure poet to the maiming of the poor man’s feet. From the missed train to the incorrect cigarettes.

Also found written in the back of the doctor’s copy of The Rubaiyat were four cryptic lines and two telephone numbers, one belonging to an ex-army lieutenant, Alf Boxall, and the other, an ex-nurse who lived in Glenelg. She told police she had owned a copy of The Rubaiyat when she lived in Sydney during World War 2, working at the Royal North Shore Hospital, but had given it to a friend named Alf Boxall. She had met Boxall at Sydney’s Clifton Gardens Hotel and, on their second meeting, had given him the book because he was leaving for active service. After the war she’d moved to Melbourne, married, had children and, when contacted by Boxall, declined to continue their relationship. When shown a bust of the dead man the woman couldn’t confirm that it was Alf Boxall.

Still, Alf Boxall became the best contender for mystery man title until he was found very much alive, working in Sydney at the Randwick Bus Depot, still in possession of his copy of The Rubaiyat. Inside the front cover the ex-nurse had copied verse 70 from the book:

Indeed, indeed, Repentance oft before

I swore – but was I sober when I swore?

And then came Spring, and Rose-in-hand

My threadbare penitence a-pieces tore.

She had then signed it ‘JEstyn’. When questioned about this verse Boxall claimed he didn’t know what significance it had. He told police he had no knowledge of the dead man found on Somerton Beach. ‘Jestyn’, as the nurse became known, asked police to keep her out of the investigation, thereby avoiding any embarrassment to her new family. Police agreed, despite the fact that Jestyn may have been one of their strongest leads.

To be clear, there were two copies of The Rubaiyat, one owned by Boxall (with the copied verse and ‘Jestyn’ signature) and one found in the back seat of the doctor’s car (with the cryptic lines, phone numbers and torn page). What was the connection between these two books? Had the nurse also known the mystery man at some stage, given him a copy of her favourite book and later denied any knowledge of him? If so, how did the mystery man know her (unlisted) phone number and why did he have Boxall’s phone number (according to Boxall they’d never met)? Did the mystery man buy a copy of his ex-girlfriend’s favourite book? Did he find a cue to commit suicide in its poetic, fatalistic lines? Was it a giant coincidence (a rare book, known by very few people in Australia at the time)?

Police believed it strange the mystery man should choose to catch a bus to the suburb where the ex-nurse lived (Somerton is only a few minutes’ walk from Glenelg). Jestyn told police that when she lived in Melbourne in 1948 a strange man had asked a neighbour about her. Was this Alf, or was it the mystery man, trying to follow up on a relationship Jestyn never properly explained? Was Jestyn really trying to disguise the paternity of a child of her present marriage, and is that why police agreed to her request for anonymity?

Jestyn died in 2007 taking, many believe, a sizeable chunk of the mystery with her. Her relationship with Boxall and the Somerton man may still hold the key to solving this mystery.

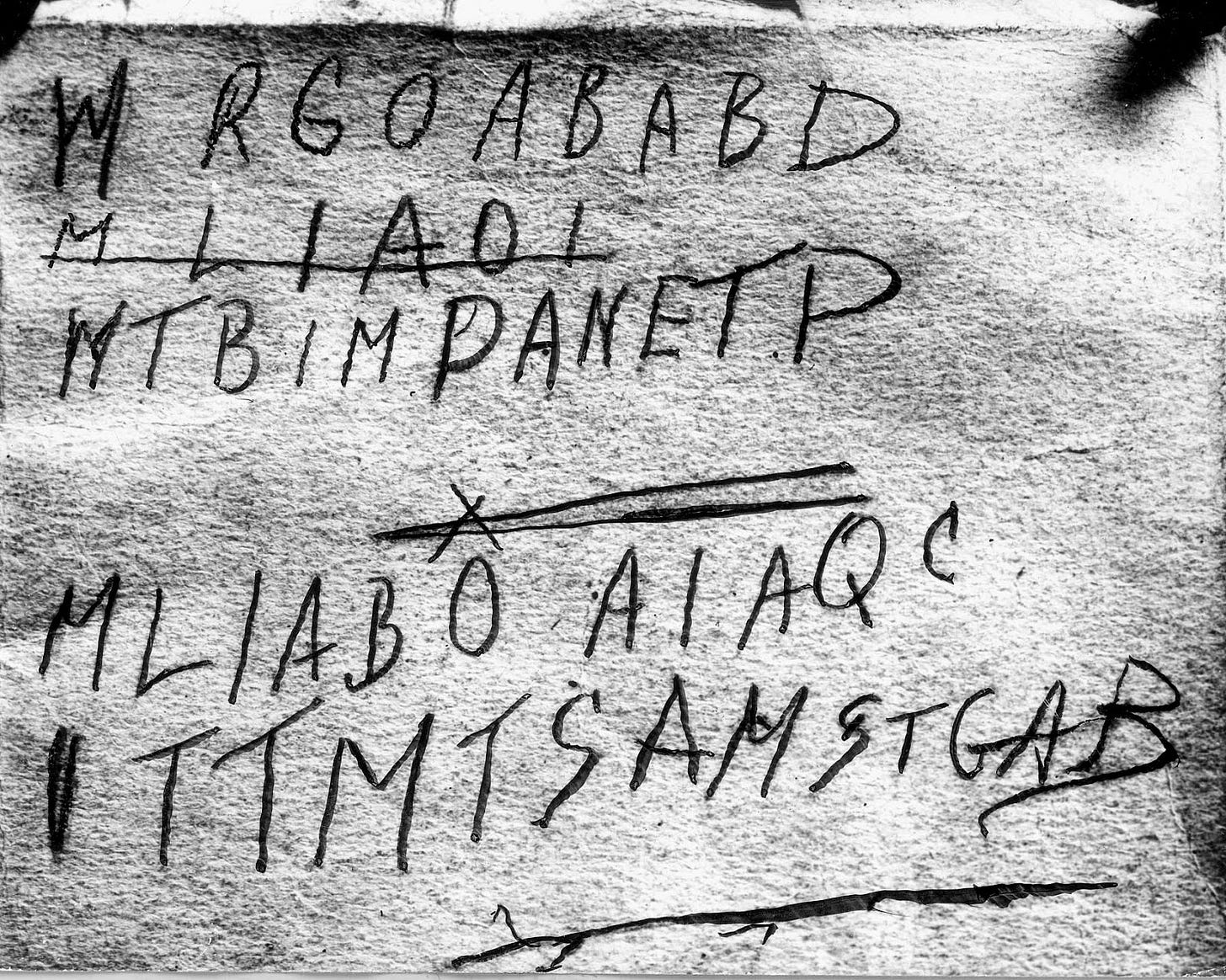

The four cryptic lines written in the doctor’s book were:

Was this the mystery man’s attempt at creating more of a mystery? Another red herring? When these lines were published in newspapers amateur codebreakers the nation over had a crack. Results ranged from, ‘Go & wait by PO. Box L1 1am T TG’ to ‘Wm. Regrets. Going off alone. B.A.B. deceived me too. But I’ve made peace and now expect to pay. My life is a bitter cross over nothing. Also, I’m quite confident I’ve this time made Taman Shud a mystery. St. G.A.B.’ I personally like the latter – the idea that this man knew he was muddying the waters. The only problem is working out how such a long message came from such a short code.

Gerry Feltus, a detective originally involved in this case, was interviewed a few years ago for an article in The Weekend Australian. In reference to these cryptic lines he said, ‘Those letters have to mean something. I try to keep away from it because I know the more you look at it the more you can become obsessed by it.’

The mystery man’s body was buried in Adelaide’s West Terrace cemetery in 1949. The headstone reads: ‘Here lies the unknown man who was found at Somerton Beach, 1 December, 1948’. The South Australian Grandstand Bookmaker’s Association paid for the burial and the Salvation Army conducted the service. Three days after the burial the inquest into the mystery man’s death was reconvened but the coroner couldn’t make any finding on the man’s identity or cause of death. He pointed out that the man seen alive by John Lyons on Somerton Beach on the evening of November 30 wasn’t necessarily the man found the next morning, as no one had seen his face.

The brown suitcase was destroyed in 1986 and many statements have been lost from the police file in the intervening years. A bust of the man (which still contains hair fibres imbedded in the plaster) is now in the Adelaide Police Museum. Gerry Feltus believes that modern DNA techniques may still help reveal the man’s identity.

Feltus, along with Len Brown, another detective who worked on the case, believe the stranger may have been from the Balkan states. In 1948 these countries were mostly under Communist rule, and they were unable to make inquiries there. Brown believes it was a case of suicide. He puts the secrecy down to the fact that the man wouldn’t want to have disgraced his family. Feltus believes it’s more than this. ‘Why would he go to the elaborate lengths he did and create this mystery if he wanted to kill himself?’ he said. Regarding ‘Taman Shud’ he says, ‘Perhaps someone gave him the piece of paper and said, Go to the beach and meet a guy who has the rest of the book… Did he meet him? Or perhaps the book was thrown into the car because he knew it would be found and get publicity and the person for whom the code letters were meant would read them in the press.’

One popular theory states that the mystery man was a spy. In April 1947, the US Army’s Signal Intelligence Service discovered that top-secret material had been leaked to the Soviet Embassy in Canberra from Australia’s Department of External Affairs. The US responded by banning the transfer of sensitive information to Australia from the US, and Australia reacted by setting up the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO). Was Alf Boxall involved in Australian military intelligence, and did he have something to do with the mystery man’s death? Was the mystery man a Soviet or Eastern-bloc spy? Had he been to Woomera, gathered information, and returned to Adelaide, where he was murdered?

There are dozens of questions that remain unanswered. Was the man a local? If so, why did no one recognise him? If not, why did no one recall his arrival, or if he drove, where was his car? The man was clean-shaven with a cutthroat razor and strap. If he was a recent arrival, where did he shave? There were no facilities at Adelaide Station and no hotels or boarding houses recalled the man. Why did he not keep the stub for his suitcase? Did he give it to a second party? What did the mystery man do at Somerton Beach (if indeed he was at the beach) from lunchtime on November 30 until his discovery?

It’s easy to imagine the mystery man’s final hours. I can see him sitting on the Somerton bus reading The Rubaiyat, scribbling the four cryptic lines with a mischievous grin. I can see him tearing the final page and putting the piece of paper in his fob pocket, preparing himself psychologically for his own end. I can see him getting off the bus and walking down the road, feeling in his pocket for the poison he’d bought on board his merchant ship. Perhaps it was intended for his unfaithful lover (did she live at Henley Beach?) but he’d decided to use it himself. I can see him sitting on the beach looking out, thinking of his distant home, wondering, What’s the use of going on, it’s just more struggle? I can see him waving at John Lyons and then later, before the cold of evening, getting up and walking to a deli, buying a pasty, returning to the beach and eating it. And then waiting for night, for an empty beach, unwrapping the poison and placing it on his tongue. Closing his eyes. Losing consciousness as his fingers opened and the poison wrapper blew away down the beach.

Or maybe I’m wrong.

Information still comes to light. Years after the man’s death a female receptionist at the Strathmore Hotel on North Terrace said she’d become suspicious (it was never explained why) of a well-spoken man who was staying in room twenty-one days before the body’s discovery. She had ordered a search of his room and found a black case containing what she thought was a hypodermic needle. The man checked out on November 29 or 30. Again, more questions. If she’d been so suspicious, why didn’t she come forward at the time? Was the man just a surgeon, a doctor, a diabetic, a drug addict, or was he the source of the mystery man’s poison, or poisoning?

In June 1949 the body of a two-year-old boy, Clive Mangnoson, was found in a sack in sand-dunes at Largs Bay, a few kilometres north of Somerton. His father, Keith Mangnoson, was found beside him, unconscious. The father was given medical attention and eventually transferred to a mental hospital. Both he and his son had been missing for four days, and the coroner determined that Clive had been dead for approximately two days before he and his father were discovered.

Keith Mangnoson’s wife, Roma, said she believed the disappearance of her husband and son had something to do with Keith’s attempt to identify the mystery man. Mangnoson believed he was Carl Thompsen, a man he’d worked with in Renmark in the late 1930s. After Keith had approached the police she’d seen a man lurking around their house in Cheapside Street, Largs Bay, and had almost been run down by a masked man driving a cream-coloured car. She stated, ‘The car stopped and a man with a khaki handkerchief over his face told (me) to keep away from the police, or else.’

Despite forensic testing, the police were never able to ascertain the cause of Clive Mangnoson’s death. Had the boy been killed with a similar ‘invisible’ poison to the mystery man? Had his father, hiding a secret he shared with the mystery man, suffered a mental breakdown, taken his son, killed him, and attempted to kill himself? Who was the masked man? And what about the common thread of beaches and sand dunes?

For years after the mystery man’s burial there were reports of an old woman putting flowers on his grave. Police even staked out the grave but never found her. Was she just a good Samaritan, or perhaps the mystery man’s Henley Beach lover?

One thing’s for certain – some stories don’t have an ending, and when we finally realise this, we turn them into myth. But the mystery man was a breathing, dreaming, walking human being, full of urges, frustrations and problems we can’t help him with anymore. When we talk about him, we talk about ourselves – and the great stage-managed mystery of our own life and death.